Health, Safety and Environment Bulletin Dec 2018

Assume at Your Peril

An inbound tanker loaded with condensate was waiting at the entrance of a buoyed channel for a harbour pilot to embark. The pilot was on board an outbound container ship. It was a calm, clear night with good visibility.

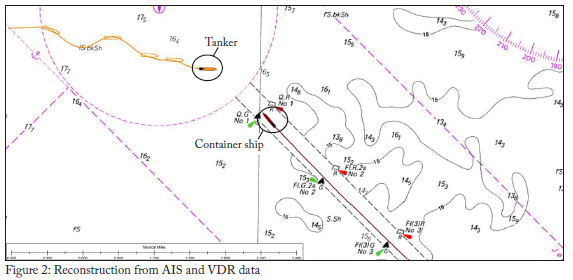

As the tanker waited, the skipper of a tug with a tow 1.3nm to the west of the entrance to the buoyed channel (Figure 1) called the port control by VHF radio and requested permission to cross the pilot embarkation area. The VTSO asked the tug’s skipper “can you see the big tanker waiting?” The tug’s skipper advised that he could, and the VTSO instructed him to “cross 1nm astern of the tanker.” The tanker’s master heard part of this radio exchange and assumed that the VTSO was talking to the container ship. He assessed that in order to pass astern of his vessel, the container ship would alter course to port on clearing the channel. The tanker’s engine was put to ‘dead slow ahead’.

As the container ship neared the end of the buoyed channel, the pilot advised the vessel’s master that it was time for him to get off. He also advised the master that the tanker would wait clear of the channel. The container ship’s speed was reduced and the pilot disembarked onto a launch. At the time, the tanker was visible and on radar 2.9nm off the container ship’s port bow. However, the radar target was not selected as an ARPA target and the tanker was not transmitting on AIS. Once the pilot launch was clear, the container ship’s master increased the vessel’s speed. By eye, he estimated that the tanker would pass about 1.5 cables off the container ship’s port side.

The tanker’s master saw the container ship pass between the last of the channel buoys (Figure 2) and became concerned when it did not alter course to port as he had expected. He called the port control and the following exchanges ensued in rapid succession:

| VTSO | Container ship this is port control |

| Container ship

(OOW) |

Port control this is container ship. Good morning |

| VTSO | Are you clearing to starboard please? We have the tanker there coming to enter the channel… |

| Pilot (on pilot

launch) |

Container ship, Hard to starboard! Hard to starboard! Hard to starboard! |

| Tanker

(master) |

Hard to ******** starboard Hard to starboard. |

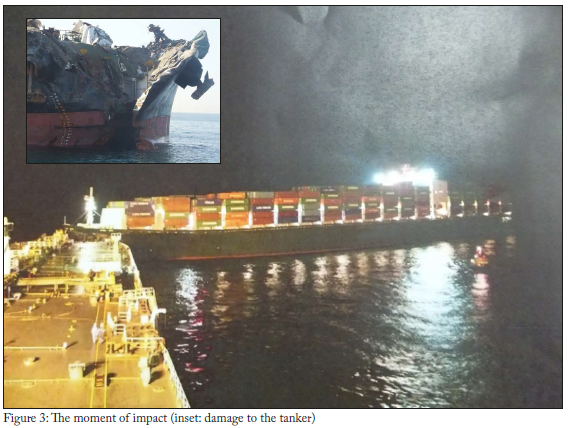

Twelve seconds later, the container ship’s master ordered “OK hard to starboard.” He then exclaimed “what’s that?” Three seconds later, the container ship and the tanker collided bow to bow (Figure 3), resulting in severe damage (Figure 3 inset) to both vessels.

The Lesson

- Manoeuvring safely in or near port areas relies to a large extent on good communications between masters, pilots and VTSOs. Discussing intentions resolves ambiguities and ensures that everyone concerned shares the same ‘mental model’, whereas taking something for granted is fraught with danger. Tell if you know and ask if you don’t; assumptions make fools of even the most capable and experienced.

- A pilot’s disembarkation and the ordering of ‘full ahead sea speed’ are frequently accompanied by a sigh of relief and anticipation of the next port of call. However, although a more relaxed focus is a natural reaction, it can never be justified while other vessels or navigational dangers are in close proximity. Regardless of how straightforward a situation might appear, the need for careful monitoring and a proper lookout is never-ending.

- Frustration and irritation inevitably result from delays in pilot embarkation and vessel entry. However, slowly creeping closer towards congested or confined areas does little to improve the situation. Very little time is saved, there is every chance of getting in the way and escape options are usually reduced.

- AIS has certain advantages over ARPA and, except for security reasons or specific exemptions, the system should always be operated on board ships on which it is required to be carried. Otherwise, valuable information – such as vessel names and status, heading and speed – is denied to others.

(Source: MAIB Safety Digest)

What’s Killing Our Seafarers?

It is easy to forget the strength and brute force that the ocean can render. Few appreciate this more than the seafarers that ply the world’s waterways in support of global trade and economic growth. Ships are not designed for the calm waters of a protected harbour.

As a community, we have recognised the need to improve the safety of life at sea. Our present collective international efforts started in earnest in 1948 when the SOLAS Convention was first adopted at the International Maritime Organization’s predecessor, the International Maritime Consultative Organisation (IMCO). Where early SOLAS requirements focused on materiel standards, more recent updates include operational issues through the International Safety Management Code; crew training and competency issues through the Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers Convention and most recently, the safety and welfare through the International Labour Organisation’s Maritime Labour Convention.

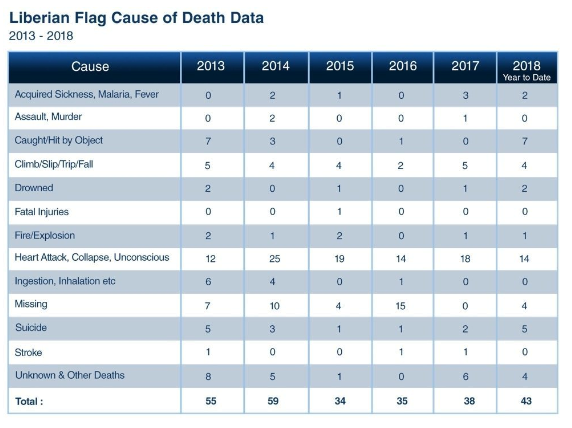

But we should ask ourselves, have we gone far enough —do we go far enough— to look after the safety of those that ensure the reliable and efficient delivery of raw materials, commodities and finished goods? At the Liberian Registry, we hold a weekly management meeting and a standing item on the agenda is a summary report on seafarer casualties. Unfortunately, this is a weekly reminder of the inherent dangers and the difficulty of working in remote areas of the world. Rarely a week goes by where we are not required to investigate the death of a seafarer.

No one expects to go to sea and not return home. Tragically, it is a living fear for those family and friends that every seafarer leaves behind as he or she starts a new multi-month contract. We consider it an inherent and globally shared passion to prevent accidents that cause injury and death. As such, we felt it would be useful to share the following Liberian Flag Cause of Death data we have collated for the last five years so that, we, as an industry, can try to make sense of these facts, figures and trends.

The very nature of shipping, and other industrial jobs, is that the environment comes with risk. Working with machinery, chemicals, fuel, and gases in unforgiving surroundings means small accidents and oversights can have terrible consequences. Anyone who has served at sea understands this. The climb/slip/trip/fall numbers are a reminder to us all of what can happen when ‘everyday’ mistakes occur.

Seafarer health, welfare, and mental illness has been a regular topic of coverage in the trade press and, from the figures carried above, it appears this is an area that rightly requires attention; it is the largest killer at sea by these records. The occurrence of heart attacks and other similar health-related incidents may not be a surprise given the increasing age of seafarers. To a degree, we are taking common onshore ‘middle-age’ problems to sea.

According to our investigations, it is also likely that many of the missing crews are victims of suicide (though there is no enough evidence to classify their deaths as such). Solving this problem might require a rethink on how we address training and health education for seafarers and masters. Onshore everyone can access doctors, counselors, and (dare I say it) online information about health issues. At sea things are different and employers and fellow seafarers do have a duty to each other to ‘red flag’ health and mental wellness concerns…because no one else can. But to do this crew must be supported by training and onshore empathy when issues are highlighted.

It is not enjoyable task writing about what is killing our people. But it is vital that we share and talk about this information, and that we continue to highlight where improvements need to be made.

(Source: Splash 247.com)

Healthy Heart – Healthy You

Keeping your heart healthy, whatever your age, is the most important thing you can do to help prevent and manage heart disease.

Heart disease and heart complications continue to be a regular cause of incidents notified to the Club. These incidents range across the full spectrum of heart health including but not limited to atrial fibrillation, angina, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, abnormal heart rhythms and myocardial infarction (heart attack).

The Club has observed that a recent number of cases have involved younger seafarers. A recent incident involved a crew member in his mid-twenties repatriated due to Wolff-Parkinson White Syndrome, a relatively common disorder where an additional electrical connection leads to the heart beating abnormally fast, in an abnormal rhythm. This illness is present at birth (congenital), although symptoms may not develop until later in life.

Another case involved the death of a 35 year old crew member due to a suspected heart attack. The seafarer had a family and personal history of controlled hypertension (high blood pressure) and was classified as overweight but not obese.

The term ‘heart disease’ is often used interchangeably with the term ‘cardiovascular disease’. Cardiovascular disease generally refers to conditions that involve narrowed or blocked blood vessels that can lead to a heart attack, chest pain (angina) or stroke. Other heart conditions, such as those that affect your heart’s muscle, valves or rhythm, also are considered forms of heart disease.

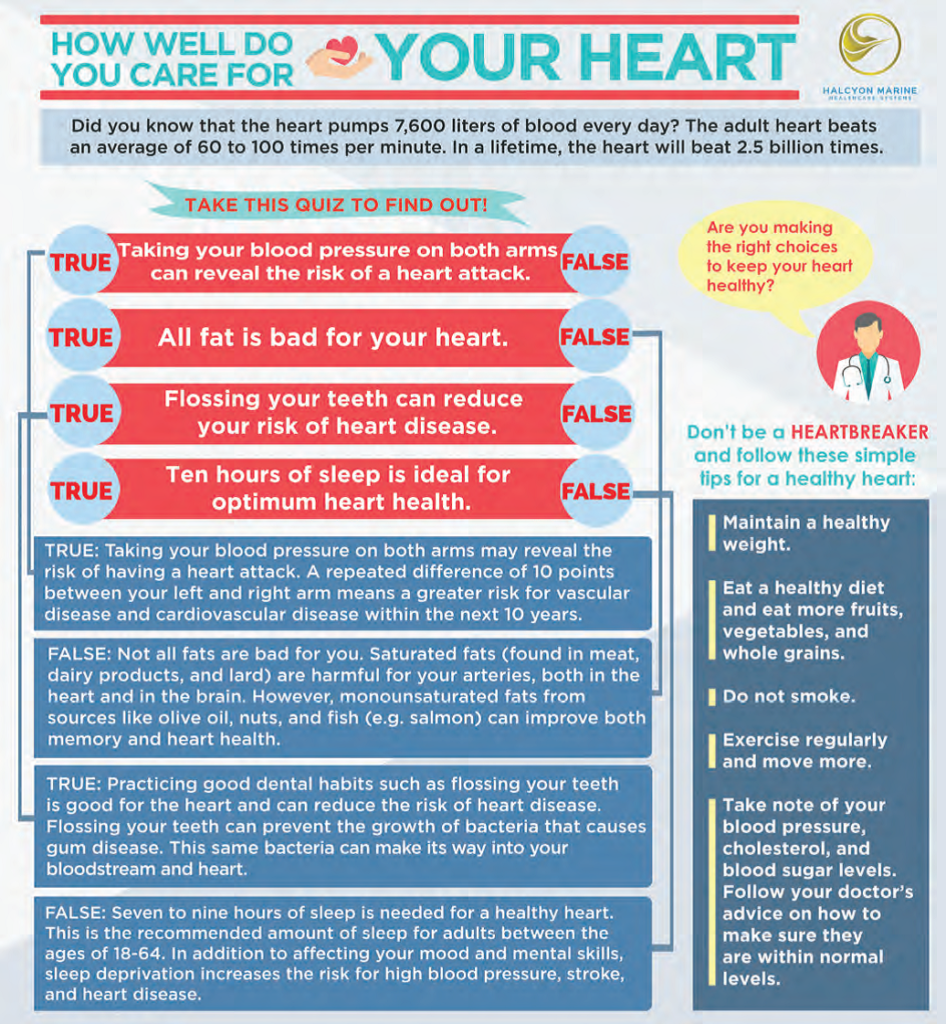

Healthy lifestyle choices can positively reduce the risk of getting heart disease, and for those at risk already, it can help to prevent deterioration of the condition.

Lifestyle Factors

There are six main lifestyle factors that can increase the possibility of developing coronary heart disease:

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High cholesterol

- Smoking

- Weight and body shape

- Diabetes

- Lack of physical activity

Ten rules for a healthier and longer life

- Stop smoking

- Eat a balanced diet

- Check your body mass index (BMI): BMI = mass (kg) / height (m2)

- Normal 18.5 – 25kg/m2

- Overweight 28 – 30 kg/m2

- Obesity >30 kg/m2

- Reduce alcohol intake

- Try to sleep at least 7 hrs per night

- Exercise at least 20 minutes a day

- Learn to cope with stressful emotions

- Maintain a healthy blood pressure –140/90 and above is considered hypertension (high blood pressure)

- Maintain good sugar control, particularly if you are diabetic

- If you have a medical condition, see your doctor at least once a year

Symptoms

Coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, heart attack – each type of heart problem requires different treatment but may share similar warning signs:

- Shortness of breath

- Palpitations (irregular heartbeats, or a ‘flip-flop’ feeling in your chest)

- Discomfort, pressure, heaviness, aching, or pain in the chest, arm, or below the breastbone

- Rapid or irregular heartbeats

- Weakness or dizziness

- Nausea

- Dizziness

- Sweating

- Swelling of ankles and abdomen

- Cough that produces white sputum

(Source: UK P&I Club)

Marine Debris: How long until it’s gone?

Plastics are the most common form of marine debris. It is estimated that 8.8 million metric tons of plastic waste are dumped in the world’s oceans each year. They can come from a variety of land and ocean based sources, enter the water and impact the ocean ecosystem. Once in the water, plastic debris never fully biodegrades.

In fact, just 5% of the world’s plastics are recycled effectively, while 40% end up in landfill and a third in fragile ecosystems such as the world’s oceans. According to a WEF report, there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean by 2050. Specifically, the report finds that the use of plastics has increased twentyfold in the past half-century and is expected to double again in the next 20 years.

This infographic illustrates how long it takes for our daily garbage found at the ocean – not only plastics – to decompose.

So, if we drop a plastic water bottle today, this will be still floating somewhere and will not be completely gone until the year 2468! Even then, this specific bottle will not completely decompose; it will become micro-plastics…

Before you throw something into the trash, just think whether it can be recycled, reused or composted! Certainly, we need a different kind of economy promoting sustainable practices to prevent and recycle waste much more. Producing less waste is a win –win situation for the society.

Increasing levels of debris in the world’s seas and oceans is having a major and growing economic impact.

However, it is not only the responsibility of governments to provide economic incentives and a different regulatory landscape to change the current situation. Everything starts from how we behave in our daily lives. The reality is that we are not going to stop using plastics, but we can start using them more responsibly and overall change the way we discard waste products.

(Source: Safety4Sea)

Severe Burn from Short Circuited Li-Ion Battery

What happened?

A crew member suffered severe burns when a Lithium-Ion battery on his person exploded and caught fire. The crew member was about to do the last task of the shift. He picked up a set of keys and a spare battery for his vaporizer from the table and put them in his pocket. He heard a loud bang and surprised, looked around to see the origin of the sound, and only then finding out that he was on fire. A motorman working nearby came to his aid and together they managed to get his boiler suit off. They saw the burning battery on the deck and stamped out the fire. Further assistance was called, and first aid was applied. The injured person was medevac’d shortly after to a shore-based hospital, where he was treated for 10 days before being repatriated to his home and undergoing further treatment.

What was the cause?

The metal keys created a short circuit with the battery. Carrying the battery in his pocket with the keys enabled the keys to provoke a ‘thermal runaway’ by either puncturing the outer shield or by making a connection between the plus and minus layers; the exact cause could not be determined conclusively.

What went wrong?

The crewman was carrying the Li-Ion battery loose in his pocket together with metal keys. This caused a short circuit of the battery and initiated a ‘thermal runaway’, which caused the battery to burst explode into flames.

When he picked up his belongings, he stated that he was not even aware of the battery being amongst his belongings, he just scooped it all into his pocket. It was noted that:

- There was no box used for carrying the Li-Ion battery;

- There was only one safety warning provided, which was actually written on the battery. No information had been provided by the supplier of the equipment of which the battery was a part.

Actions taken and lessons learned

Lithium-Ion batteries, which are more and more common in devices used onboard, are not controlled properly and it cannot always be expected that the proper and correct information has been provided by the supplier.

Lithium-Ion batteries sometimes come in size and design similar to ‘AA’ sized batteries and as such can be easily confused with a normal alkaline battery, and thus the risk associated is also confused.

It is recommended to:

- Ensure that all persons are properly informed about the hazards associated with Lithium-Ion batteries. This should include the charging, handling and storage and the risk associated with carrying the batteries loose in pockets;

- Consider more thorough control of small personal electronic devices using Lithium-Ion batteries.

(Source: IMCA Safety Flash 28/18)