Health, Safety and Environment Bulletin Sep 2019

Crew Fatality during Tank Cleaning

The incident

On 31 August 2018, Key Fighter berthed alongside Crude Passion at Averøy, Norway, where it discharged its remaining cargo of Rapeseed oil.

Before sailing for Erith, UK, 58 m³ of slops, reported to contain a mixture of tank wash water and vegetable oils, were transferred from Crude Passion to Key Fighter.

The slops, which were being loaded in cargo tank no. 5 port, were noted by the crew members to have a pungent odour of ‘rotten egg’.

“He (the chief officer) stated that he had advised the AB and the painter to be very careful with the entry into cargo tank no. 5 port, due to the ‘rotten egg’ smell reported earlier. He recalled that he had also requested that the cargo tank is well ventilated, to keep the bridge informed and use personal gas detectors. He wrote down these instructions on a sheet of paper, which was left in the CCR, and then went to bed.”

Following departure and while on passage, the slops were pumped out at sea and the crew started cleaning the cargo tanks.

The second officer remained alone on the bridge. He confirmed that from the bridge, he could see the floodlit deck area and the cargo tank entry lids, including those fitted on cargo tank no. 5 port.

“However, he neither saw the watch changeover nor any crew member on deck; he actually assumed that if there was no one to be seen on deck, then everyone must be in the CCR. During the duration of his watch, there were no communication checks between the bridge and the cargo tank cleaning team. Moreover, the section in the cargo tank entry permit was filled neither with cargo tank entry nor exit details for the remaining time of the navigational watch.”

The following morning, at about 0405 , two crew members involved in the cleaning and washing of cargo tanks were found lying motionless inside cargo tank no. 5 port. The crew members were airlifted to a hospital in Norway.

Probable cause

The immediate cause of the accident was a fall from a height which led to fatal injuries, according to the Accident Investigation Board of Norway.

“It was considered unlikely that both crew members would have fallen in a similar manner without the presence of additional factors. The MSIU was informed that post mortem tests could not confirm the presence of H2S gas.”

The injuries may have been fatal, but based on the circumstances of the accident, the autopsy report indicated that it was possible that the cause of death was either intoxication by Hydrogen Sulphide (H2S), or suffocation due to lack of oxygen.

Conclusions

- There were neither management directions nor guidelines available for the loading of slops;

- Key Fighter undertook to receive a considerable amount of slop from Crude Passion without slop specific MSDS and without management directions or guidelines;

- Audit records indicated that the loading of slop was neither raised by the master nor identified during the audit;

- There were no records of pre-cleaning meeting and it is likely that the atmosphere monitoring of cargo tank no. 5 port during the cleaning process was not addressed in the toolbox talk;

- There was no effective supervision of the cargo tank cleaning and ventilation operations / ongoing atmosphere monitoring for toxic gas were not carried out;

- The general risk assessment document was not signed by the deceased crew members;

- Personal gas detectors were not worn by the crew members who accessed the cargo tank;

- Ventilation of cargo tank no. 5 port was carried out using portable gas freeing fans rather than the fixed Novenco type centrifugal fan;

- The officer responsible for ensuring that all parts of the entry permit were properly completed, was available neither on deck nor in the CCR during the cargo tank cleaning;

- The cargo tank entry permit was approved without all parts of the permit completed;

- The loading of slops ‘routine’ per se, and the related success (in terms of achievable goals) may have led to informal ways on how to complete the job;

- Given the success of past procedures and given that there were no disconfirming cues where being received by the crew members which would have suggested not to access the cargo tank, the decision to access the cargo tank was not rejected.

Other findings

- Analysis of the record of rest hours of the crew members involved in the cargo tank cleaning operations indicated that the documents were in compliance with the MLC and STCW Convention requirements;

- The tank entry procedure and the tank entry permit were in line with IMO recommendations and the guidance offered in ISGOTT Chapter 10;

- Although the SMS recommended pneumatically powered lights for a satisfactory level of illumination inside the cargo tank, these were not available on board;

- There was no dedicated look-out on the bridge during the hours of darkness;

- The pungent odour of H2S gas coming from the slops did not trigger a realisation of the potential hazard to the crew and the loading of slop was not terminated;

- The loading of slops and its discharging at sea, was not recorded in the vessel’s Cargo Record Book;

- There were no management guideline and the carriage of slops was not authorised in the vessel’s Certificate of Fitness.

Actions taken

During the course of the safety investigation, the Company adopted the following safety actions:

- Frequent visits on board by Company representatives to observe and discuss shipboard operations;

- Additional training offered to crew members;

- Analysis of all Company procedures; and

- Crew conferences on board, aiming to improve on safety.

(Source: Safety4Sea)

Vessel on Master’s Orders and Pilot’s Advice

“Vessel on Master’s orders and Pilot’s advice” – a common entry used in the bridge logbook when entering and leaving a port, but what does it mean?

It’s well known that in the vast majority of places around the world the presence of a pilot on the bridge does not relieve the Master or officer in charge of the watch from their duties or obligations for the safety of the ship. Yet there are still many cases where the Master appears to relinquish control to the pilot or fails to challenge a potentially unsafe instruction, sometimes resulting in an incident.

Follow or not?

If the pilot informs the Master to conduct a manoeuvre that results in an incident, will that prevent the Master being responsible? Almost certainly not, because ship management and navigation in most cases remain the responsibility of the Master.

This is illustrated by lines 170 and 171 of the NYPE 46 Charterparty which reads:

“…The owners to remain responsible for the navigation of the vessel…same as when trading for their own account….”

In the un-safe berth case The Stork, one of the issues was whether the Master acted reasonably when following pilot’s advice on anchoring despite the Master having issues with the instruction. The court noted that pilots possess intimate local knowledge and concluded, “Of course, the master cannot transfer his responsibility to the pilot, but a master would be very imprudent if in a place of this sort he disregarded the advice of those with local knowledge unless he had very good reason for doing so.”

This means that the Master – in consultation with the bridge team – should assess any instruction given by the pilot to make sure that if the pilot’s instruction is carried out, the vessel will be safe.

In another case, The Vine, it was considered whether a terminal had a system to ensure the Master was informed of important features of the berth. The court decided that: “The fact that the pilot may have such knowledge does not detract from the importance of the master having such knowledge. For the master is responsible for the safe berthing of his vessel even though he may be advised by the pilot…Of course, orders will be “advised” by the pilot who in reality will determine the appropriate orders but the master must be in a position to reject the pilot’s advice if he considers it to be unsafe.”

Another common misconception is that the pilot’s suggestion constitutes an employment order which enables an owner to hold the charterer responsible or be indemnified. Mr Justice Staughton was clear in The Erechthion that whilst the orders of a harbour master to proceed to an anchorage were employment orders, the pilot’s suggestion as to where the vessel should anchor was a matter of navigation so the ultimate responsibility lies with Master. Although the charterer may pay for the pilot, this does not make the pilot the charterer’s servant. Accordingly, this does not mean that the charterer will be responsible to the owner for the pilot’s negligence (see Fraser v Bee [1900] 17 T.L.R. 101).

The certainty of disagreement

Disagreeing with a pilot is easier said than done. Commercial pressure often makes ignoring the pilot’s instructions very difficult. Masters are only too aware of the commercial consequences of missing a schedule or creating delays. However, it is very important that this is not an overriding factor in the Master’s decision.

Should the Master choose not to follow a pilot’s instruction, and this results in a delay or extra expenditure, a dispute will most likely follow. But if the Master chooses to follow the instruction and it results in an incident, again a dispute will follow.

Inevitably, there is a high risk of a dispute regardless of what choice the Master makes. So how can a Master best equip themselves?

SOLAS on your side

SOLAS Chapter V regulation 34-1 states:

“the owner, the charterer, the company operating the ship, or any other person SHALL NOT prevent or restrict the master of the ship from taking or executing any decision which, in the master’s professional judgement, is necessary for the safety of life at sea and protection of the marine environment.”

Considering SOLAS chapter V is one of the best tools at a Master’s disposal, they should ensure they remain in command and make a reasonable choice based on safety alone.

It is also imperative that the Master gathers relevant contemporaneous evidence to prove that the choice not to follow the pilot’s instructions was reasonable. For example, this can include:

- Risk assessments

- Tidal data

- Charts

- Passage plans

- Navigation warnings

- Echo sounder records

- VDR data

- Statements

- Photographs

- Checklists

- Master pilot exchanges

- The bridge logbook entries

Courts in the most part will sympathize with a Master who has considered the safety of his crew and the vessel and acted reasonably, even when there is a delay or additional expenditure as a result.

Should the Master follow the pilot’s instruction without thinking fully of the safety factors, and an incident occurs, then SOLAS Chapter V will work against the Master.

(Source: North P&I Club)

Take the Long View on Tanker Attacks

Political and naval tensions continue to ratchet up in the Gulf, but shipowners and operators must hold their nerve.

The shipping, oil and insurance sectors remain exposed to a heightened threat of further action after this year’s series of low-level attacks on tankers in the Gulf. The energy industry has, however, been here before.

The history of seaborne trade suggests that we are in for a long haul. A series of possibly loosely coordinated ‘warning’ attacks can continue for months or years without any lethal escalation to armed conflict, even as political tensions are ratcheted higher. With so much sabre-rattling by politicians, it’s important to keep a sense of perspective. Oil exporters are largely plying their trade as usual, albeit with extra security and insurance costs.

War risk

During the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war, when 50 ships were lost in the so-called Tanker War, shipping continued despite the fact that insurance rates spiked. The pricing of risk today is at the highest possible levels without a war actually being declared. Tehran views a long-term crisis just below the level of a war as better than waiting for US sanctions to slowly cripple its economy.

Even so, this year’s attacks on oil tankers have already sent up oil prices, war risk and insurance premiums and the blood pressure of all those involved in bulk transport by pipelines and ship. However, the attacks have come at a time when market conditions have been able to dampen the impact.

“The initial response of oil prices to the attacks in the Strait of Hormuz has been surprisingly muted because the markets are focused on bearish fundamentals,” explains Kiran Ahmed, lead industries economist at Oxford Economics. “Oil demand is lacklustre, oil production in the US is strong and OPEC is reining in its production, so there’s a lot of spare capacity and inventory levels are high.”

Despite this, the war risk premiums owners pay every time a supertanker sails through the Gulf have now soared to more than $185,000 up $50,000 since the attacks began in May.

A fact of life

This year, six oil tankers have been damaged, exposing the security frailties of a key shipping route. The attacks near the Strait of Hormuz – a choke point through which a fifth of the world’s oil exports flow – appear to be an attempt to test the resolve of the US and its allies without sparking a war. US national security agencies believe proxies sympathetic to, or working for, Iran are behind the attacks.

“These developments are nowhere near the scale of threat to shipping during the Tanker War in the 1980s,” says John Stawpert, manager of environment and trade at the International Chamber of Shipping. “Brent crude prices are currently below $70 a barrel, whereas a year ago they were more than $100. While this is very concerning, it’s a fact of life that the shipping sector has to deal with threats across the world.”

Comac McGarry, senior analyst at consultancy Control Risks, adds: “We have received a large number of requests from clients who are increasingly concerned about the immediate threat to their vessels, cargo and business in the Gulf region. We are helping clients understand the immediate impact these maritime attacks are having on shipping, as well as the broader geopolitical tensions that underpin them, because understanding and monitoring those tensions is key to informing decisions around preparation for any escalation.

“Businesses are reviewing their commercial continuity and contingency plans in readiness for an escalation towards a full-blown conflict, although we believe this remains unlikely.

“The attacks are likely calculated to build leverage for Iran in negotiations. The most likely scenario is that the attacks will continue to occur amid periods of high tension, but we believe an outright conflict or the closer of the Strait of Hormuz remain unlikely, barring a miscalculated or misinterpreted attack.”

(Source: Marine Professional)

One Small Step for a Man – a Giant Leap for Safety?

Two crew from the engine room department were on deck, tasked with preparing the manifold for bunkering. As they were laying out a canvas under the bunker manifold, one of the men stepped backwards and slipped from the manifold grating, which did not have a railing.

He fell back towards the deck about one meter below, and instinctively tried to catch himself on the grating. As he did so, his left-hand ring finger was trapped between the gratings, as shown in the simulation photos below. When his weight came on the trapped hand he sustained a cut.

The victim was immediately given first aid. Although minor, this injury could easily have been much worse, even requiring repatriation had the finger been broken.

Lessons learned

Mundane tasks that have always been done a certain way can nonetheless present risks that are invisible to the crew. How would you prevent this accident from happening?

- It is critical to keep one’s situational awareness while performing any task.

- Practicing on-site (and on-going) risk assessments to identify all potential hazards at the work site is a key safety behavior.

- IMO has now defined ‘safety’ as ‘the absence of unacceptable levels of risk’. Is your ship safe?

(Source: MARS Report 2019)

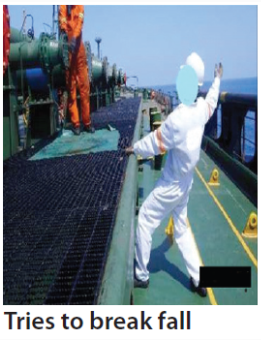

Alarming Spike in Dengue Cases

After a drop in the number of dengue cases in 2017-18, 2019 has seen a sharp increase and countries in South America and South-East Asia are currently the most seriously affected.

Dengue is a viral disease transmitted by infected mosquitoes and can be life-threatening. Dengue flourishes in poor urban areas, suburbs and the countryside but can also affect more affluent neighbourhoods in tropical and subtropical countries. The infection rates are higher outdoors and during daytime. There is no vaccination for dengue, and the best way to prevent it is to protect against mosquito bites.

Precautions for ships trading within mosquito zones

Prior to visiting affected areas:

- Monitor for official advice regarding any ongoing outbreaks. Contact a medical practitioner if in doubt.

- Review all the ports to be visited in that area and evaluate the risk. Consider the length of stay in an affected area, time spent at sea, in port, on rivers, etc., as well as planned shore leave by the crew.

- Inform the crew about the risks present and the precautions to be taken as well as actions to be taken if illness occurs at sea. Stress that a headache, fever and flu-like symptoms are always grounds for contacting the medical officer.

- Ensure sufficient supplies onboard of effective insect repellents (e.g. those containing DEET, picaridin or IR3535), light coloured boiler suits, porthole/door mesh screens and bed-nets.

During a visit to affected areas:

- Implement measures to prevent mosquito bites, including:

- keep all openings closed and operate air conditioning at all times;

- stay indoors, in accommodation and engine room areas, as much as possible;

- wear loose-fitting light-coloured clothes when proceeding onto the deck and other open areas;

- use effective insect repellents on exposed skin and/or clothing as directed on the product label; and

- when using a sunscreen, apply sunscreen first, followed by repellent.

- Remove pools of stagnant water, dew or rain to prevent the vessel creating its own mosquito breeding grounds.

- Pay particular attention to wet areas of lifeboats, coiled mooring ropes, bilges, scuppers, awnings and gutters. “Even a bottle cap can contain enough water for a mosquito to breed!” says the WHO.

- Use an insecticide spray to eradicate mosquitos found inside accommodation or other areas.

After a visit to affected areas:

- Seek medical advice over the radio if dengue is suspected on board.

- Place the patient under close observation and undertake the required onboard treatment, preferably in close co-operation with a medical doctor.

- The patient should rest and drink plenty of fluids. Paracetamol can be taken to bring down any fever and to reduce joint pains. Aspirin, ibuprofen, or other NSAIDs should not be taken since they can increase the risk of bleeding.

- Medical evacuation may be the only solution if the patient’s condition does not improve.

(Source: GARD)