Health, Safety and Environment Bulletin Mar 2019

Lubes Headache Brewing

Fuel choices have obscured the complex issues over lube selection ahead of IMO 2020. The vast column inches spent on next year’s fuel conundrum for owners have obscured another mounting headache come the onset of the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) global sulphur cap.

Shipowners need to be aware today that come January 1, 2020 their bills for lubricants are likely to spike and the availability of the right lube to match the brave new low sulphur world could well be in short supply.

Warns Caroline Huot, global head of lubricants at Cockett Marine Oil, an affiliate of Vitol and Grindrod, “Cylinder oils availability will be just as much of a risk to slowing global trade when IMO 2020 starts as sourcing suitable compliant ship fuels in the desired location.”

Huot, a 20-year veteran of the lubes business, tells Maritime CEO in a special IMO 2020 compliance guide launched yesterday: “Owners in general, except the very big ones with sufficient in-house lubrication expertise, have understandably been obsessed by fuels and have not greatly thought things through regarding lubes and IMO 2020.”

Explaining the situation, Huot starts with two stroke engines for non-scrubber fitted ships, i.e. more than 90% of the global merchant fleet.

Cylinder oil issues for these ships can be divided in two – for vessels built pre-2010 where the impact is lesser and for more modern vessels built after 2010.

All ships without scrubbers will have to change their lubricants. Typically ships with engines built pre-2010 use today cylinder oil with a base number (BN) of 70 when they burn high sulphur fuel, whereas more modern ships fitted with long strokes and super long stroke engines will use BN 100 cylinder oil as they face the risk of cold corrosion particularly when slow steaming.

“The problem is,” explains Huot, “once you have to adopt burning 0.5% sulphur fuel globally and permanently you will need also to adopt permanently lower BN cylinder oils, BN 40 and BN 25.”

Modern vessels face either a risk of cold corrosion (not enough alkalinity to neutralise the corrosive effect on liners), something Huot describes as a dangerous phenomenon and a silent enemy or these ships risk the fast generation of hard deposits on the piston crown generated by excess or unused BN additive. Ships from next year face damage either to liners or to rings and bearings.

Huot is concerned with the lack of enough operational experience in using these lower number BN oils. Shipping has been using lubes with lower BN (BN 40) for more than a decade, but only on niche trades or regions such as South America and West Africa where fuels are naturally low sulphur and require such a product.

However, because of their niche nature, these BN 40 oils have struggled in the past to get easy OEM approval as it was difficult to find vessels staying long enough or burning permanently LSFO to comply with the number of running hours required by the field tests.

More recently with the creation of emission control areas (ECAs) where the use of marine gas oil or ULSFO is mandatory, it has been necessary to use even lower BN cylinder oil (BN 15-25) and again the use of such cylinder oil – except for smaller vessels trading the ECAs permanently – is not extensive when it comes to bigger bore engines and global trading patterns.

There are a few mitigating solutions to fight the oncoming confusion and chaos likely in early 2020, according to Huot.

Owners and managers will need to make the most of used oil analysis to check and anticipate as much as possible cold corrosion (specific drain oil analysis) as well as additives hard deposit traces and get used to trend monitoring as well as be ready to use a way higher number of analysis than ever before, which will have an impact in terms of costs.

People will need to be trained both onboard and on shore to analyse the results of the reports and follow up the trend very carefully to avoid costly maintenance issues and then carry out feed rate adjustments accordingly as well as other mitigating measures.

There’s then the issue of costs. Not unlike the low sulphur fuel prices that are so obsessing the minds of the world’s shipowners now, the industry needs to be aware that as this previously niche BN 40 lubrication goes global as it is already priced today higher than usual cylinder oil, it is unlikely to see any adjustment downwards. On the contrary, the price is likely to go up.

Moreover, its availability everywhere is by no means guaranteed with Huot predicting it’ll take anywhere from nine to 18 months after January 1 next year before supply chain disruptions ease and global availability is ensured.

“Historically any roll out of a new grade of cylinder oil has been very slow,” the lube veteran points out.

“We expect the start of 2020 to be very hectic in terms of availability and potentially subsequent breakdowns.”

And for those who have bought a scrubber? Can they breathe easy? To begin with, yes, but like with the fuel scenario, as BN 40 becomes more commonplace, say by 2021, then the availability and price of today’s traditional cylinder oils, the BN 70 and 100 varieties, may likely change dramatically too.

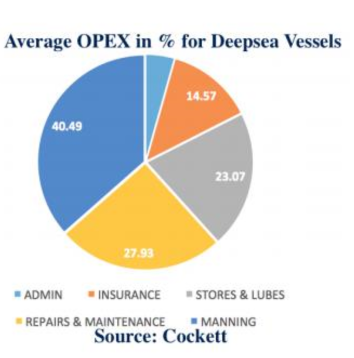

IMO 2020’s chicken and egg head scratching over fuel prices next year looks like it is very much being replicated in the lubes sector too, something of serious concern for owners given that lubricants today make up 10 to 13% of a typical ship’s daily opex.

(Source: Splash 24/7)

When Your Watch is Dragging…

Narrative

Strong winds and tidal streams were forecast when the master of a small general cargo vessel was forced to change his plans and anchor overnight in an estuary to await a bunker barge. The vessel had not been able to take bunkers when alongside, and had insufficient fuel to reach its next port.

After sailing with a river pilot on board, the vessel proceeded to an anchorage as advised by the VTS. It was then anchored 40 minutes before low water in a depth of 12m using 5 shackles of cable. Several other vessels were also at anchor close-by. Shortly afterwards, the master handed over the bridge watch to the second officer, the pilot disembarked, and the main engine was stopped.

While on watch, the second officer remained on the bridge correcting charts. He was alone, and checked the vessel’s position every 30 minutes. During one of the checks, the second officer noticed that the vessel had moved significantly closer to one of the other anchored vessels. As predicted, the easterly wind was now force 9 and the rate of the north-westerly flooding tidal stream had increased to over 2.5kts. The cargo vessel had been dragging its anchor for about 10 minutes at a speed of up to 1.4kts, and the second officer immediately alerted the master and called the engineer to start the main engine.

By the time the cargo vessel’s engineer had dressed and started the main engine it was too late to avoid a collision. The cargo vessel struck the other vessel at anchor, which then also started to drag. Both vessels then collided with a third vessel, which was also at anchor. Nobody was injured but all the vessels sustained damage (see figure).

Figure: Damage to the small cargo vessel

Figure: Damage to the small cargo vessel

Figure: Damage to the small cargo vessel

The Lessons

- The ability of an anchor to bite and continue to hold relies heavily on sufficient length of chain cable being used, particularly when strong winds and tidal streams are experienced and the tidal range is large. In such conditions, the more anchor cable used the more likely a master’s rest will remain undisturbed.

- During anchor watches, bridge watchkeepers frequently use the time to catch up with a variety of tasks. Usually this is time well spent. However, position monitoring remains a key task, the frequency of which depends on local conditions and circumstances. The longer the interval between checks, the further a ship might have dragged towards danger.

- Automatic anchor watch alarm functions that are available on GPS receivers appear to be seldom used on merchant ships, even those not equipped with ECDIS or ECS. Yet such facilities, which are relatively quick and straightforward to set up, can provide real-time warning and a greater peace of mind.

- The options available when a ship drags its anchor are extremely limited if its propulsion is not available. Occasionally, when conditions dictate, this means having engines at immediate readiness.

(Source: MAIB Safety Digest 1/2019)

Finger Injuries

Loss of Fingers

The multi-national crew of a large, modern, cargo vessel had undertaken a lifeboat drill while alongside in port. They were in the process of recovering the lifeboat when a deck cadet’s fingers became caught under the fall wire, which resulted in two of his fingers being traumatically amputated.

The cadet was given immediate first-aid on board, then taken ashore to the local hospital for emergency treatment before being repatriated home a few days later to recover.

The regular launching and recovery of the ship’s lifeboats formed part of the ship’s training schedule. As the ship was alongside for the afternoon, permission was obtained from the port authority to launch the ship’s starboard lifeboat to the water.

The chief officer gave the team involved a safety brief and toolbox talk about the lifeboat drill, and his intention for the crew to grease the fall wires afterwards. Four crew members then embarked into a service boat that was brought alongside the quay, and two tins of grease with greasing rollers were brought to the boat deck by another crewman.

Under the command of the chief officer, the bosun lowered the empty lifeboat to the water. The four crew members boarded the lifeboat from the service boat and completed in-water running tests. Because of a slight swell in the harbour, it was decided not to take the lifeboat away from the ship’s side. When the tests were complete, the crew made the lifeboat ready for hoisting and disembarked into the service boat.

Once the lifeboat was ready, the chief officer gave the order and the bosun started to hoist the lifeboat using the electric motor. Unnoticed by the bosun, the cadet stepped forward to grease the fall wire by letting it run through his hand close to the winch drum as the boat was being heaved up. Without warning the cadet’s hand became stuck to the wire and his fingers became trapped under it as it was being wound onto the drum. Because his hand was so close to the drum, his warning shouts did not give the bosun enough time to stop the hoist motor before his fingers were trapped and traumatically amputated between the wire and the drum.

The Lessons

- It is essential that seafarers are familiar with the life-saving systems on board their ships and that they perform regular drills. Abandon ship drills should be planned, organized and carried out so that the recognized risks are minimized. In this case, the lifeboat drill followed correct procedures: the boat was lowered empty, before a dynamic risk assessment identified that taking it off the hooks when it was in the water would introduce an unnecessary hazard. The benefits of taking a moment to re-assess site safety cannot be overstated.

- Although most wire rope is supplied to ships pre-lubricated, protecting exposed wire rope is a necessary part of the maintenance procedure to prolong its life. Greasing a wire by running it through someone’s hands can be very dangerous, particularly if the grease is old, cold, thick and sticky; and gloves and skin can be caught on a broken wire. Greasing a moving wire should only be undertaken with great care after thorough risk assessment, and by using a brush, spatula or an automated lubrication system. Not, as in this case, by hand.

- There were two tasks being undertaken. First, the lifeboat drill, and second, the greasing of the wires. Because the toolbox talk included them together, the cadet was unclear when to undertake the greasing task. Great care must be taken to ensure all participants fully understand their role, particularly on vessels with mixed nationalities. Trainees and less experienced crew require closer supervision and help. Toolbox talks must be short, simple and focused on one subject at a time.

(Source: MAIB Safety Digest 1/2019)

Fingers Squeezed by Crane Wire

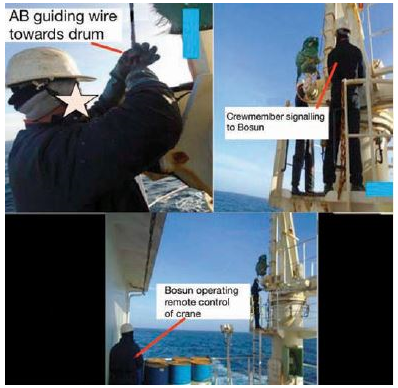

Three crew members were in the process of reeving in the topping wire of the provision crane. One crew member was guiding the wire on to the warping drum while another signalled to the bosun who was using a remote control on deck to run the drum.

At one point, wire pinched the fingers of the crew member guiding it, causing him to cry out in pain.

The bosun reacted quickly but, out of confusion and panic, he operated the crane in the wrong direction, which resulted in the crew member’s hand being further squeezed by the warping drum. First aid was immediately administered. Because of the severity of the injury, however, the victim had to be signed off from the vessel and sent ashore for further medical attention.

The company investigation found that the bosun, who had just joined the vessel, was not sufficiently familiar with the safe and smooth operation of the crane.

The Lessons

- A toolbox meeting that exposes the job hazards and mitigation measures can help reduce accidents.

- Co-ordination and communication techniques should be agreed upon while performing any job that involves more than one person.

- Proper familiarisation should be given to any newly joined crew members. For example, the first few operations of the crane by a newly joined member of crew should be done under supervision of a qualified officer or other experienced crew member.

- Operating procedures and the instructions on the crane’s key controls (with photographs) could be posted near the provision crane operating position for easy reference.

(Source: MARS Reports 201817)

Importance of Food Safety Management

A ship’s engine may run on fuel oil, but the crew runs on food. Like the engine’s fuel supply, the crew’s food must be safe and be of the right quality. The recent outbreak of listeriosis in South Africa, which has reportedly killed almost 200 people, serves as a timely reminder that prevention is better than cure when dealing with food safety.

Poor food safety management through improper storage, preparation and handling can result in food poisoning. As well as the problems this causes to the individual crew member, a severe outbreak on board could affect the safe operation a vessel.

Ships’ crews must be made aware of the steps that can be taken to reduce the risk of falling to foodborne illnesses.

Common Illnesses

Most cases of food poisoning on vessels are caused by bacteria. Even where there are good standards of hygiene and food safety practices on board, the crews are also at risk of eating contaminated food whilst ashore. Some of the more common illnesses are outlined below.

Listeriosis

Caught from eating food containing the listeria bacteria, it is most often caused by eating contaminated ready-to-eat meat products and unpasteurised dairy products. Symptoms are flu-like and include high temperature, vomiting and diarrhoea. A healthy person typically does not need medical treatment and symptoms will usually go away within a few weeks.

Salmonella

Salmonella bacteria live in the gut of many farm animals; therefore salmonella is caught from eating contaminated eggs, poultry and other animal products. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, headache and diarrhoea.

E-Coli

A bacterial infection caused mainly by the E. coli O157 strain, found in the gut and faeces of many animals, particularly cattle and sheep. Most often associated with fresh fruit and vegetables, undercooked meat and unpasteurised dairy products. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, headache and diarrhoea.

Cholera

Outbreaks of Cholera usually occur where there is poor sanitation. It is mostly caused by contaminated water and food including rice, vegetables and seafood. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhoea and abdominal pain which can result in severe dehydration.

Norovirus

Usually associated with cruise ships or densely populated buildings, Norovirus is a common stomach bug which usually clears within a few days. Typically spread by close contact with an infected person, touching contaminated surfaces or eating food that has been prepared by an infected food handler. Symptoms include nausea, extreme vomiting, watery diarrhoea and abdominal pain.

Practical Steps to Safer Food

Simple steps will help ensure food and water on board is safe and remains safe. This is particularly important for those preparing and handling food on a daily basis. The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued valuable advice on food safety and identified ‘five keys to safer food’. These can form the basis of a vessel’s food safety management system.

“Keep clean”:

- Wash your hands before handling food and often during food preparation

- Wash your hands after going to the toilet

- Wash and sanitize all surfaces and equipment used for food preparation

- Protect kitchen areas and food from insects, pests and other animals

“Separate raw and cooked”:

- Separate raw meat, poultry and seafood from other foods

- Use separate equipment and utensils such as knives and cutting boards for handling raw foods

- Store food in container s to avoid contact between raw and prepared foods

“Cook thoroughly”:

- Cook food thoroughly, especially meat, poultry, eggs and seafood

- Bring foods like soups and stews to boiling to make sure that they have reached 70°C. For meat and poultry, make sure that juices are clear, not pink. Ideally, use a thermometer

- Reheat cooked food thoroughly

“Keep food at safe temperatures”:

- Do not leave cooked food at room temperature for more than 2 hours

- Refrigerate promptly all cooked and perishable food (preferably below 5°C)

- Keep cooked food piping hot (more than 60°C) prior to serving

- Do not store food too long even in the refrigerator

- Do not thaw frozen food at room temperature

“Use safe water and raw materials”:

- Use safe water or treat it to make it safe

- Select fresh and wholesome foods

- Choose foods processed for safety, such as pasteurized milk

- Wash fruits and vegetables, especially if eaten raw

- Do not use food beyond its expiry date

If a crew member thinks they have become ill through food or water contamination, they must report it. They should keep hydrated and follow any medical advice given. It is important to determine what food and drinks they have taken so the source of the illness can be identified. Avoid contact with other crew and foodstuffs in order to contain the illness and prevent an outbreak.

(Source: North of England P&I Club & World Health Organisation)